The 2020 Pelican Journal

The 2020 Pelican Journal gives you an idea of what you are missing if you are not a member of the League!

Source: The Pelican, Nurses' League Journal 2020. pages 28-31.

Christmas Washout

A meeting took place in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh on 24 July 1962; the remit was to establish a Regional Poisoning Treatment Centre in RIE in association with Regional Poisons Information Service. RIE joined a UK-wide system; identical information systems were also in place in Guy’s Hospital, London, and in Cardiff and in Belfast.

Ward 3 had originally been set apart for the management of patients with incidental delirium, and patients from other parts of the hospital (often surgical wards) who were unmanageable because of delirium or very disturbed behaviour. In an era of very few (almost no) male nurses, 3 had a male orderly on duty at all times to support nursing staff in giving what could be very difficult patient care.

The Regional Poisons Treatment Centre was established in Ward 3 under the auspices of Dr. Henry Matthew, who introduced the concept of general supportive therapy rather than using active therapy with unproven treatments. The Scottish Poisons Information Bureau was established and run from the ward; computerisation of the National Poisons Service was led by Dr. Proudfoot.

Outside normal working hours, calls were taken by the ward’s medical and nursing staff; often they also became involved during the day. Their responsibility was to read out, accurately for the caller, the specific information on a product, filed alphabetically in heavy, unwieldy Kalamazoo binders stored in a cupboard beside the specially designated (red) telephone.

In our day most patients were admitted to Ward 3 during the night, and because there were no general intensive care beds in the hospital, patients requiring intubation and ventilation remained in Ward 3. (Some readers may remember the gradual evolution of intensive care/therapy throughout the hospital through creation of small specialized units within appropriate areas such as the renal department, cardiology etc.) The clicking and wheezing sound of those old green Bird ventilators is unforgettable! Sometimes patients developed acute renal failure and haemodialysis was then usually performed. It could be very busy!

On admission, nearly all patients were subjected to gastric lavage with an extremely wide-bore rubber tube. A large jug of water was poured down into the stomach via a large funnel attached to the top of the tube. Then the contents, were returned - into a large bucket on the floor by dropping the funnel down below the level of the patient’s stomach. Not very glamorous for life-saving nursing and certainly not comfortable for the patient! Unlike present times, gastric lavage was usually done whether the patient consented or not. Unfortunately, depending on the patient’s stomach contents the process could prove very nauseating for all participants. Staff tended to develop coping mechanisms, usually involving humour. One Christmas when staff came on duty they were met with a big sign: Hope this Christmas is not a washout.

It made us all smile.

Dr Matthew called the management of patients intensive supportive care. Physiological support could involve ventilation (as indicated above) and maintaining blood pressure, often simply achieved by elevating the foot of the bed. Monitoring and sustaining such interventions were definitely intensive.

What was not within the regime was prophylactic antibiotic therapy, bladder catheterization, or unproven scientific/clinical treatments.

In keeping with the GP prescribing habits of the time, overdoses were commonly benzodiazipines (such as Mogadon, Valium), barbiturates, tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. Triptizol) and a relatively new sleeping sedative (Methaqualone, i.e. Mandrax). Aspirin and paracetamol were also favoured by some self-harmers. In those days both of these could be bought over the counter in large quantities, loose in pill bottles. It was easy for a determined self-harmer to knock back whole bottles at a time, often washed down with alcohol. The law has changed and a restricted purchase of bubble packs of these drugs has impacted choice!

Less common poisoning events involved coal gas (which at the time was rapidly becoming obsolete), opiates and a well-known weed-killer (Paraquat).

Ward 3 had an international reputation as a leading centre of psychiatric and clinical toxicological research. Over the years very effective treatments were introduced for poisoning with salicylates, such as aspirin, and also for paracetamol, which were adopted universally. From the 1970’s probably the most important clinical advances in management of drug overdosage and poisoning in Ward 3 included the first introduction of a new treatment (N-acetylcysteine) for paracetamol poisoning.

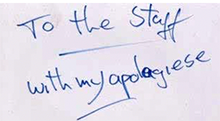

The actual mortality rate for patients admitted to Ward 3 with self-poisoning was very low. However, many were habitual self-harmers. This author can recall Keith (not his real name), an exceptional young man, who after a disturbed and unhappy start in life had been discharged from the Danish navy and the British army. The standard diagnosis of psychopathic personality disorder was applied and Keith was detained in the Carstairs State Mental Hospital for eleven months. Between 1972 and 1978 he was admitted to Ward 3 on eighty-two occasions for self-poisoning. On thirty-one of these admissions he had taken paracetamol; at this time medical staff were trying to find the best treatment for severe paracetamol poisoning. Keith provided them with very useful comparative information, having received different treatments (unpleasant Cysteamine five times, Methionine once, Cysteine once and N-acetylcysteine six times). In a letter to medical staff, he stated that last on the list (N-acetylcysteine) was by far the best while first on the list (Cysteamine) by far the most unpleasant treatment. During this time Keith also had twenty known admissions for self-poisoning to the Royal London Hospital and frequent admissions to at least four other London teaching hospitals. One year he even sent a Christmas card to the staff of Ward 3. It was signed:

To the Staff with my apologies Keith.

Sadly, Keith’s career in self harm progressed to the renown deadly weed- killer (Paraquat); remarkably he survived.

Finally, he ended his life by jumping off the Forth Road Bridge at 04.00 one morning.

Some poisoning was accidental. There was one such case where a man was about to have a meal of boiled tripe, possibly after a visit to the pub. Understandably, to try to make the meal more appealing, he sprinkled it with what  he thought was a container of table salt. After a few mouthfuls he noticed with horror that instead of salt, he had laced his meal with “Harpic” - the well-known lavatory cleaner! The containers were almost identical in size, shape and colouring.

he thought was a container of table salt. After a few mouthfuls he noticed with horror that instead of salt, he had laced his meal with “Harpic” - the well-known lavatory cleaner! The containers were almost identical in size, shape and colouring.

According to his GP’s letter he drank copious amounts of water and fortunately he came to no harm.

According to his GP’s letter he drank copious amounts of water and fortunately he came to no harm.

Not all accidental poisoning had such a good outcome. There was a very sad fatal case where that infamous weed-killer (Paraquat) had been left in an old lemonade bottle. A young boy picked it up on a hot summer’s day and took a small mouthful. Sadly for him, even after all the work from all the staff, including a pioneering treatment of a lung transplant,  they were unable to save his life.

they were unable to save his life.

Ward 3’s working environment was strange and stressful. Resources were inadequate and often conditions were adverse. There was

continual awareness that anything could happen at any time. The characteristics of this special group of patients were often, as in Keith’s case, down to their personal unhappiness and awful circumstances. At times, staff were hard pressed to cope with some of the hopelessly inadequate souls and the multiple repeaters.

What made it possible was that they functioned as a team; it was a jolly place to work and was always vibrant, rewarding and compassionate.

Ria Tocher (Tierney, 1977) With thanks to contributors Professor Laurie Prescott, and Ward Sisters Heather Hamilton (Parr, 1956) and Elaine Roscoe (Barr, 1969).